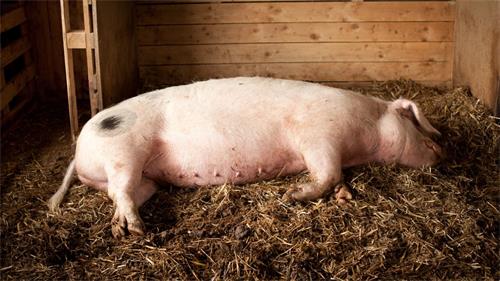

Raising pigs involves careful monitoring of the breeding and gestation process, particularly during the final weeks before farrowing (giving birth). One concerning but not uncommon situation for swine producers is when a sow appears to be overdue — showing fetal movement but not initiating labor at 125 days of pregnancy. This can be worrying, especially for small-scale farmers or first-time breeders. Understanding this phenomenon requires insight into normal swine gestation, possible complications, and how veterinarians and producers around the world approach diagnosis and intervention.

In this article, we explore the potential reasons why a sow might still be pregnant at 125 days, still show signs of life in the womb, and yet not farrow. We will combine veterinary science with international swine management experience to provide practical, evidence-based insights for resolving such cases.

Understanding the Normal Gestation of a Sow

Under typical conditions, the gestation length for pigs is around 114 days, often expressed as “3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days.” This period may vary slightly depending on breed, parity (whether it’s the sow’s first pregnancy), litter size, nutrition, and environmental stress.

In general:

Most sows farrow between days 112–115.

Farrowing after day 116 is considered delayed.

By day 120 and beyond, intervention is usually recommended.

When fetal movement is still visible or palpable at day 125, it usually means the fetuses are still alive, but something is delaying parturition.

Reasons for Delayed Farrowing with Fetal Movement

1. Inaccurate Breeding Records or Mistimed Mating

One of the most common and benign reasons is simple error. A miscalculation in breeding dates — such as recording the second or third mating as the actual conception date rather than the first — can push the expected due date back by several days. In some extensive systems or multi-mating strategies, it’s possible that ovulation and fertilization occurred later than expected.

Global Practice Insight:

In countries like Canada and the Netherlands, where breeding is often done via artificial insemination (AI), records are strictly kept. However, delays in ovulation or misinterpretation of estrus signs can still lead to wrong gestation expectations.

2. Hormonal Imbalance

Successful farrowing relies on a well-regulated hormonal cascade involving prostaglandins, estrogen, progesterone, and oxytocin. Any disruption—due to endocrine disorders or stress—can delay uterine contractions and cervical dilation.

For example, excess progesterone (the hormone that maintains pregnancy) beyond the normal gestation window can inhibit labor initiation.

Veterinary Tip:

European swine veterinarians often assess hormone profiles if sows show no signs of labor by day 118, especially when fetal movement is present.

3. Uterine Inertia (Primary or Secondary)

Uterine inertia is a condition where the uterus fails to contract effectively. This may occur in overweight sows, under-exercised sows, or those carrying extremely large litters.

Primary inertia: The uterus never initiates contractions.

Secondary inertia: The uterus begins to contract but stops due to fatigue or obstruction.

Signs include restlessness without visible straining, or weak, irregular straining that doesn’t progress to delivery.

In both cases, fetal movement may continue since the piglets are still viable, but without strong contractions, farrowing cannot begin naturally.

4. Malpositioned Fetuses or Overdeveloped Fetuses

When fetuses grow beyond a certain size, especially in cases of small litters, they may be too large for natural delivery. Alternatively, fetuses in abnormal positions (breech or transverse) may block the birth canal, delaying farrowing.

International Experience:

Swine producers in the U.S. and Germany frequently perform transabdominal ultrasonography with portable veterinary ultrasound to assess fetal size and position late in gestation. It helps detect potential dystocia (difficult birth) before labor even starts.

5. Environmental and Stress Factors

Environmental elements—such as high temperatures, sudden cold, poor ventilation, or crowding—can stress the sow and affect the hormonal balance necessary for initiating labor.

In tropical or sub-tropical countries, delayed farrowing has been associated with heat stress, especially in open housing systems. Research in Australia has shown that reducing heat stress with cooling systems significantly reduces farrowing delays and stillbirths.

What Should You Do If Your Sow Is at 125 Days and Hasn’t Farrowed?

1. Check Records and Recalculate

Start with the basics: review mating and AI records. If you used multiple inseminations over several days, consider the possibility that conception occurred later than originally estimated.

2. Perform a Clinical Examination

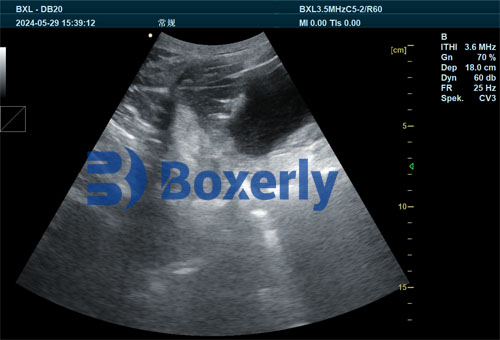

If the sow appears healthy but has not farrowed by day 116–118, a veterinarian should perform a physical and ultrasound examination.

Ultrasound can confirm:

Fetal viability (heartbeat, movement)

Fetal size

Placental structure and fluid content

Signs of infection or abnormal fluid

The B-mode ultrasound is the tool of choice. Devices like the BXL-V50, a portable veterinary ultrasound, are widely used in such evaluations. It provides high-resolution images of the uterus and its contents, helping guide the next steps.

3. Assess for Signs of Impending Labor

Veterinarians and experienced producers often look for:

Nesting behavior

Swollen, milk-producing udders

Red, relaxed vulva

Restlessness or discomfort

If none of these signs appear by day 118–120, it’s time to intervene.

4. Induce Labor (Under Veterinary Guidance)

If no complications are detected but labor has not started by day 118–120, labor may be induced using prostaglandin analogs (e.g., cloprostenol) in combination with oxytocin. This mimics the natural hormonal trigger for labor.

Warning: Induction should only be performed after ruling out oversized fetuses, infection, or obstruction. Improper induction can lead to stillbirths or uterine rupture.

5. Prepare for Possible Assisted Farrowing or C-Section

In rare cases—especially when fetal movement continues but no labor occurs even after induction—a Caesarean section may be necessary. This is usually a last resort in commercial operations but may be considered in high-value or companion pigs.

Long-Term Considerations and Prevention

Nutrition and Exercise

Ensure pregnant sows are not overfed and receive adequate exercise.

Balanced diets prevent obesity, which is linked to uterine inertia.

Accurate Breeding Management

Use timed AI protocols and estrus detection aids to improve breeding accuracy.

Maintain thorough breeding and health records.

Use of Ultrasound in Late Pregnancy

Periodic ultrasonographic exams allow early detection of anomalies.

Portable devices like the BXL-V50 enable in-field scanning without transporting the sow.

Genetic Selection

Monitor for recurrent cases. Chronic delayed farrowing may be genetic and warrant culling.

Conclusion

A sow that reaches day 125 of gestation without farrowing—but still shows fetal movement—is experiencing an abnormal but not hopeless condition. Possible causes range from simple miscalculations to complex hormonal or structural issues. With the aid of veterinary ultrasonography and proper management protocols, such cases can often be resolved safely for both sow and piglets.

International swine management practices emphasize early diagnosis, use of technology, and minimal-stress environments to avoid such complications. For any farmer, especially those in small-scale or backyard setups, knowing when to seek veterinary help and how to interpret signs of abnormal gestation can make all the difference in reproductive success.

References

Morrow, D. A. (2021). Current Therapy in Theriogenology: Swine Reproduction and Obstetrics. Elsevier.

Mainau, E., Temple, D., & Manteca, X. (2016). “Welfare implications of delayed farrowing in sows.” Porcine Health Management, 2(1). https://porcinehealthmanagement.biomedcentral.com

National Swine Resource and Research Center. (2023). “Reproductive Management in Sows.” https://nsrrc.missouri.edu

NCSU Veterinary Medicine (2022). “Use of Ultrasound in Swine Pregnancy Management.” https://cvm.ncsu.edu/swine-ultrasound-guide

link: https://www.bxlimage.com/nw/1251.html

tags: