Reproductive efficiency is one of the cornerstones of profitable dairy production. Any disruption in the reproductive cycle can have a significant economic impact, leading to delayed calving intervals, reduced milk production, and higher culling rates. One common but often misunderstood reproductive disorder in dairy cows is the persistent corpus luteum (PCL), also referred to as persistent CL or luteal cyst. Veterinary ultrasound has become a crucial tool in accurately diagnosing this condition and managing its implications. In this article, we explore how veterinary ultrasound is used to detect and monitor persistent corpus luteum in dairy cattle, with a global perspective on its causes, diagnosis, treatment, and management.

Understanding Persistent Corpus Luteum

In a normal estrous cycle, the corpus luteum (CL) forms on the ovary after ovulation and secretes progesterone to support a potential pregnancy. If the cow does not become pregnant, the CL typically regresses after about 17–21 days, allowing the next estrous cycle to begin. However, in some cases, the CL fails to regress and remains active beyond the normal cycle length, continuing to produce progesterone. This condition is known as a persistent corpus luteum.

Cows with PCL typically do not show signs of estrus (heat), which leads to anestrus (lack of observable heat) and poor reproductive performance. Persistent CL is more commonly observed in infertile or subfertile cows, particularly those suffering from uterine infections, hormonal imbalances, or postpartum complications.

The Role of Veterinary Ultrasound in Detection

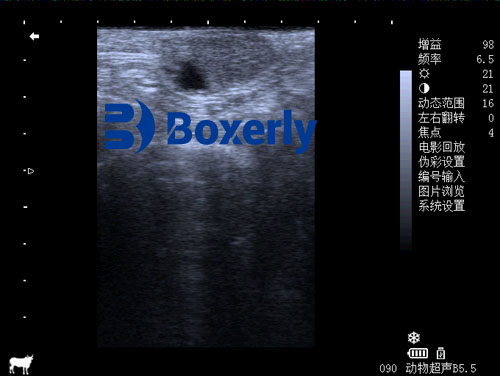

Veterinary ultrasound—specifically B-mode ultrasonography—has become the gold standard for monitoring ovarian structures in dairy cattle. When scanning a cow’s ovaries, ultrasound can reveal the size, shape, and internal structure of the CL. A persistent CL appears similar to a normal one in terms of echogenicity and structure. This means that simply identifying a CL via a single scan is not enough to diagnose persistence. Repeated ultrasonographic exams are required to determine whether the CL is failing to regress over time.

On ultrasound, a CL appears as a hypoechoic or mixed-echogenic mass on the ovary, often with a clearly defined border and sometimes with a central cavity. If this structure persists for more than 25 days in the absence of pregnancy, and no heat signs are observed, it is classified as a persistent CL. Additionally, ultrasound allows the veterinarian to assess the uterus for concurrent abnormalities, such as uterine fluid, endometrial thickening, or retained placental material, all of which may contribute to the persistence of the CL.

Global Perspectives on Causes and Risk Factors

Veterinarians and researchers worldwide have identified several key factors contributing to the formation of persistent CL:

Uterine Infection and Postpartum Complications

Chronic endometritis, retained placenta, and other postpartum uterine infections can delay or block luteolysis—the process by which the CL regresses. Studies from Europe and North America emphasize the importance of postpartum health in preventing reproductive disorders.Hormonal Imbalances

An imbalance in the secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) can disrupt the ovarian cycle. For instance, excessive LH or insufficient FSH can prevent follicular development and ovulation, prolonging CL lifespan. In Japan and the Netherlands, hormone monitoring is integrated with ultrasound protocols to diagnose such imbalances.Foreign Material or Debris in the Uterus

The presence of a dead fetus, fetal membranes, pus, or mucus in the uterus can act as a physical or biochemical barrier to luteolysis. In Brazil, studies have shown a high correlation between intrauterine debris and persistent CL, especially in pasture-based systems where uterine infections are harder to detect early.Poor Nutrition and Sedentary Management

Mineral deficiencies (particularly selenium, vitamin A, and phosphorus), poor-quality feed, or lack of exercise have been implicated in reproductive disorders globally. In India and China, where some farms still rely on traditional feeding practices, the role of nutrition in PCL occurrence has been well-documented.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

The main clinical sign of PCL is prolonged absence of estrus despite otherwise normal behavior and feed intake. Cows may appear healthy but never come into heat. This can mislead farmers into assuming the cow is pregnant.

Rectal palpation may reveal one or both ovaries enlarged with a firm, raised structure resembling a normal CL. However, ultrasound is needed for confirmation, especially because the texture and echogenic pattern of a persistent CL are nearly identical to those of a regular CL. The key lies in repeated scans that reveal no changes over time and the absence of pregnancy despite prolonged luteal activity.

Differentiation from Pregnancy

One of the most important roles of veterinary ultrasound in diagnosing PCL is differentiating it from early pregnancy. A persistent CL may be mistaken for a gestational CL if the veterinarian relies only on a single scan. This is why it is essential to examine the uterus for signs of pregnancy, such as an embryonic vesicle or fetal heartbeat. In cases of uncertainty, rescanning after 7–10 days is advised to observe any structural changes.

Management and Treatment

Fortunately, with accurate diagnosis and prompt intervention, the prognosis for cows with persistent CL is generally good, particularly if no severe underlying diseases are present.

Here are globally adopted treatment options:

Prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) Analogues

These are the most common and effective treatments. Drugs such as dinoprost and cloprostenol are administered via intramuscular injection, typically at doses ranging from 10 to 25 mg depending on the drug. They induce luteolysis and restart the estrous cycle. If the first dose is ineffective, a repeat dose may be given after 10–14 days.Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH)

GnRH or its analogues (e.g., buserelin, deslorelin) may be used to stimulate follicular development, particularly when persistent CL coexists with follicular cysts. These are typically administered at 100–250 µg intramuscularly.Estrogen Therapy

In some regions, such as South America and parts of Asia, estrogen-based treatments (e.g., diethylstilbestrol) are used to initiate luteolysis. However, this practice is declining due to regulatory concerns.PMSG (Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotropin)

In cases with secondary ovarian inactivity, PMSG may be used to stimulate ovarian activity. The typical dose is 20–30 mL intramuscularly.Comprehensive Reproductive Management

Treating the underlying cause—such as uterine infections—alongside hormone therapy improves success rates. In Europe, integrated treatment protocols that combine prostaglandins with uterine flushes or antibiotic therapy are common.

The Importance of Nutritional and Environmental Management

Preventing PCL also involves maintaining good nutritional and environmental conditions. Farmers in New Zealand and Australia have focused on balanced diets, sufficient exercise, and postpartum care to reduce reproductive disorders. Vitamins A, D, and E, along with selenium and phosphorus, play vital roles in reproductive health.

Additionally, minimizing stress, avoiding overcrowding, and monitoring postpartum uterine health can significantly reduce the incidence of persistent CL. Regular reproductive checks using ultrasound help catch these issues early, leading to better outcomes.

Case Example: Using Ultrasound for Accurate Diagnosis

On a dairy farm in Wisconsin, a 5-year-old Holstein cow showed no signs of estrus for over 50 days postpartum. Rectal palpation suggested the presence of a CL, but the veterinarian wasn’t certain if the cow was pregnant or suffering from PCL. Ultrasound revealed a well-defined CL without an embryonic vesicle. A repeat scan 10 days later showed no regression, and PGF2α was administered. The cow returned to estrus within 5 days and was successfully inseminated during the next cycle.

This example illustrates how veterinary ultrasound provides a reliable method for confirming persistent CL and guiding timely treatment decisions.

Conclusion

Persistent corpus luteum is a subtle yet impactful reproductive disorder in dairy cattle. It often escapes notice in its early stages and can significantly impair reproductive efficiency if left untreated. Veterinary ultrasound offers a non-invasive, accurate, and repeatable method for detecting and managing this condition. When combined with hormonal treatment and proper nutritional and environmental care, the chances of recovery and successful rebreeding improve dramatically.

For dairy producers around the world, integrating regular ultrasonographic monitoring into herd reproductive management is a wise investment. It ensures that issues like persistent CL are caught early, improving overall herd fertility, productivity, and profitability.

link: https://www.bxlimage.com/nw/1212.html

tags: