In commercial pig farming, optimizing reproductive performance and maximizing litter growth are crucial to overall profitability. Among the various factors influencing reproductive efficiency, the backfat thickness (BF) of gilts—especially during late pregnancy—has drawn increasing attention. As a livestock producer, I’ve often observed variations in sow performance linked to their body condition. Recently, I came across a scientific study examining whether gilts with higher backfat thickness produce more milk and, consequently, raise heavier piglets. It’s a compelling question, and the answer holds practical implications for how we manage our herds.

Understanding Backfat Thickness in Gilts

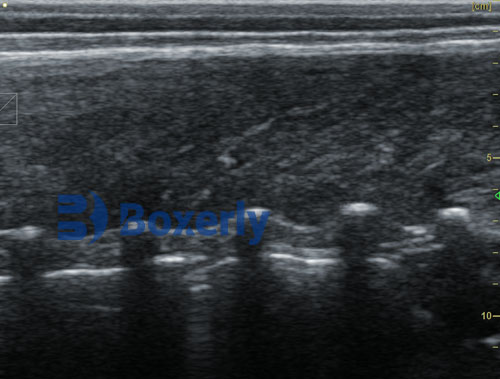

Backfat thickness refers to the layer of fat covering a pig’s back, typically measured at the P2 position (located just above the last rib). This measurement is a routine part of managing sow herds, serving as a proxy for energy reserves. On most farms, we measure backfat at critical points during the reproductive cycle: weaning or mating, pregnancy check, and entry into the farrowing room. This allows us to monitor whether a sow is gaining or losing condition—information that helps guide nutritional and grouping decisions.

Notably, both too little and too much backfat can be detrimental. Sows with low backfat at weaning often have trouble returning to estrus, while those with excessive fat at farrowing may suffer from poor lactation performance and difficult deliveries.

Backfat and Its Impact on Mammary Development

The study I reviewed compared over 350 first-time mother sows (also called primiparous sows) by grouping them according to backfat thickness at 110 days of gestation. These sows were either part of a commercial herd or participants in research trials focused on mammary development. The sows were classified into three groups based on their BF:

LOW (around 13.6–14.2 mm),

MEDIUM (17.6–18.1 mm), and

HIGH (21.8–23.4 mm).

The researchers evaluated two key outcomes:

Piglet bodyweight gain during lactation,

Developmental characteristics of the mammary glands, including parenchymal tissue, total protein, and DNA content.

The results were clear: sows with higher backfat produced more mammary tissue, total protein, and DNA—all indicators of better milk-producing potential. Moreover, litters from HIGH BF sows showed an 8.5% increase in weight gain compared to LOW BF sows. Although modest, this weight gain could significantly impact weaning outcomes over the long term.

Why This Matters for Farmers

As someone who works closely with pigs every day, I find this insight particularly useful. If gilts carry more backfat in late pregnancy—specifically in the 20 to 26 mm range—they may be better prepared for lactation, giving their piglets a better start in life. This also supports longer-term productivity, as adequate lactational performance promotes healthier sow recovery and quicker return to estrus.

However, it’s essential to maintain a balance. Gilts that are too fat can experience reduced feed intake post-farrowing, potentially limiting milk production and risking farrowing difficulties. Moreover, they tend to lose more backfat during lactation, putting their reproductive longevity at risk. Conversely, very lean sows—while more efficient in some cases—have little energy reserve to draw on during lactation. This increases the risk of reproductive failure in subsequent cycles.

The Bigger Picture: Body Condition vs. Productivity

One of the most important takeaways from this discussion is the changing role of BF as an indicator of sow body condition. In the past, backfat was the main measure used to estimate sow energy reserves. Today, lean body mass, often reflected by live weight (LW), is becoming more relevant. Still, BF remains a valuable metric—especially in gilts, where it provides a practical way to assess energy status before first farrowing.

Another fascinating insight is the comparison with other livestock, like dairy goats. Goats typically have very lean bodies with minimal udder fat, enabling high milk production. Could sows benefit from a similar body condition? Possibly—but only to an extent. Unlike goats, pigs mobilize more tissue during lactation, so having some fat reserves is necessary to support both their current litter and future breeding potential.

Practical Implications on My Farm

Based on this evidence, I’ve made some changes to our gilt management strategies:

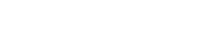

More precise BF measurements: We now measure gilts around day 110 of gestation using ultrasound to ensure they fall within the optimal 20–26 mm range.

Grouped feeding strategies: In farms where individualized feeding isn’t feasible, grouping sows by BF can help tailor feeding and prevent both over- and under-conditioning.

Breeding selection: We now pay more attention to body condition in selection criteria, prioritizing gilts that reach breeding weight with moderate backfat.

These steps have already started showing benefits. Our lactation performance has become more consistent, piglet weaning weights are trending upward, and we’ve seen a reduction in post-weaning anestrus cases.

Final Thoughts

While backfat isn’t the only factor influencing sow productivity, it is certainly a practical and valuable tool for managing herd health and efficiency. For gilts in particular, maintaining adequate backfat thickness during late gestation helps ensure robust mammary development and better piglet growth outcomes. Striking the right balance—neither too fat nor too lean—can set the stage for a productive first lactation and a long, successful reproductive career.

Reference

Farmer, C., Martineau, J.-P., Méthot, S., & Bussières, D. (2017). Comparative study on the relations between backfat thickness in late-pregnant gilts, mammary development and piglet growth. Translational Animal Science, 1:154–159. https://doi.org/10.2527/tas2017.0018